The release of a new Arcade Fire album means that it is time to blow the dust off the blog for some reflections – so to speak.

Any band who wins a Grammy for Album of the Year immediately raises the stakes for their next release. Arcade Fire’s follow up to The Suburbs does not disappoint either in its musical quality or, as we have come to expect from this band, its philosophical engagement and social commentary. In fact, some of the deepest questions of human existence are engaged in the first track, and the band never lets off the accelerator throughout the album. On Reflektor, classical mythology, existentialist philosophy and even theoretical physics come together in a complex weaving of questions and ideas that leaves the careful listener in a state of…reflection.

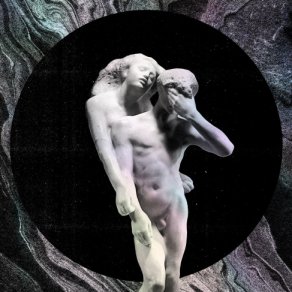

The journey into Reflektor begins on the cover. Rodin’s “Orpheus and Eurydice” recalls the classic Orpheus myth wherein the great Greek poet and musician who could charm anything with his singing, loses his wife, Eurydice, to death and Hades when she is bit by a serpent. Through the power of his singing, Orpheus persuades Hades to allow Eurydice to return to the land of the living. However, there is one condition: In leading Eurydice out of Hades, Orpheus must not look back. In a moment of weakness, just as they near the boundary, Orpheus looks back, losing Eurydice forever. For Arcade Fire, the Orpheus myth leads into philosophical speculation about the enduring nature of love, an exploration of whatever is on the other side of the experience after death, and the implications of each for contemporary life.

The second philosophical concept that drives Reflektor comes from the 19th century Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard. In the lead single, “Reflektor” and several times throughout the album the singer refers to “the reflective age.” In 1846, in a literary review essay entitled “The Present Age and of the Difference Between a Genius and an Apostle,” Kierkegaard considers the present age “reflective” because it is “devoid of passion, an age which flies into enthusiasm for a moment only to decline back into indolence.” Rather than being revolutionary, inspiring individuals who lead a generation forward, the present age “is an age of advertisement, or an age of publicity” where anticipation abounds among the public but nothing happens. Many of the songs on Reflektor explore the existential and cultural effects of living in an “age” that has become, in lead singer Win Butler’s estimation, worse than Kierkegaard could ever have imagined [1].

The third theme that pervades Reflector, which is a common point of cultural criticism for Arcade Fire, is a questioning of traditional forms of Christian faith. The spectre of bad religion haunts nearly every track on the album. Whether it is the detachment of American religion from its foreign mission fields (“Here Comes the Night Time”), the conservative social mores of many contemporary Christian groups (“Here Comes the Night Time”, “We Exist”, “Reflektor”, “Joan of Arc”), simplistic and exclusivist notions of heaven and the afterlife (“Reflektor”, “Afterlife”, “It’s Never Over”), or social alienation and the mistreatment of others because of the influence of conservative religion (“Normal Person”, “Flashbulb Eyes”, “Porno”, “We Exist”), Arcade Fire calls conservative Christianity to reflect upon the character of its witness within the world. As with The Suburbs, Arcade Fire does not offer any direct constructive proposals for a way out of the ills unleashed upon the world bad religion, but there is implicit within these critiques some semblance of a way forward by at least raising the questions.

These three threads are woven together in varying combinations throughout Reflektor and provide a helpful way to get to the heart of Arcade Fire’s “reflections” on contemporary culture, which is just a “reflective” way of saying “us.”

By way of example, the lead single, “Reflektor,” engages the Orpheus myth by placing the song in the context of a love affair, which just happens to take place in “the reflective age” – our theme from Kierkegaard. These two threads intertwine as a man and woman – our modern day Orpheus and Eurydice – “[fall] in love” but yet are “alone on a stage.” Their love began while “staring at a screen” and as they relate with one another their “signals… are deflected,” which may represent the public “stage” of electronic media by which they connect and simultaneously calls into question the quality of their connection. As a result, their love is constantly threatened to “break into bits.” These two strands of inquiry raise the question: What is the nature of love in the modern era? Can this digitized, reflective-era love span the distance between not only day and night (“entre la unit, la unit et l’aurore”) but also endure the chasm between life and death (“entre les royaumes, des vivants et des morts”)?

Engaging more directly the Kierkegaardian notion of the reflective age, the song “Reflektor” also calls into question the quality of our understanding. In a reflective age, according to Kierkegaard, innovation is impossible because the courage required to revolutionize is not valued. So, there is no genius, but repeated versions of our current state of understanding. A great example of this is apparent in the realm of technology. Today’s processor-based computing machines (everything from smartphones, to laptops to server-quality systems) are microscopic versions of the same transistor technology that were built into the first computers in the mid-20th century. The basic logic is the same; the only thing that has changed is the complexity of the form. So computing devices, in this example are “just a reflection of a reflection of a reflection.” The forms are simply efficiencies, but not leaps of innovation. Reflektor suggests that the ideological mold of the reflective age can become so strong that it can feel like being trapped in an ideological prism, where everything you see is a manifestation of the same basic set of ideas. In such a “prism” it appears difficult to find an escape.

The same applies in the realm of Christian faith. In the song, Butler looks to the “resurrector” as a solution to the dilemmas of life and love in a reflective age. The concept of a God who raised Jesus from death, as it turns out, is a pretty revolutionary idea. It is the reality, in fact, that turned the world on its head in the time of Jesus and continues to have transformative power. But it turns out in the singer’s quest that even the idea of God is also “just a reflektor.” The import of this idea echoes one of the modern criticisms of all religion. Religion, it is held by modern skeptics, is simply a projection of human values onto the heavens. God and gods, in this evaluation, are reflections of us. What Butler suggests here, I believe, is that theology and Church practice can get itself in a state where its most revolutionary elements (God, truth, goodness, beauty, etc.) can lose their power. Echoing Kierkegaard again, the power of any particular reality or idea to transcend human understanding and thereby transform the hearts and lives of people makes it revolutionary. When the church forgets this and subjects its theology to a political and social reality, even something as revolutionary as the resurrection becomes reflective. The implied question is can Christian faith combat the reflectiveness of our age by working within its own revolutionary ideals to change the present culture?

Taking a similar approach to unpacking the other songs on the album results in the same richness of cultural critique as Arcade Fire explores these themes in their latest meditation on contemporary culture. That will be the task of the next few posts in this series.